The US federal government hasn’t balanced its budget since 2001. On its own, this is not necessarily cause for concern. In the context of higher interest costs and a national debt exceeding 120% of gross domestic product (GDP), however, alarm bells are beginning to ring.1

We believe the market is mispricing the risks embedded in US government debt (Treasuries). A persistent budget deficit and mounting national debt risk stymying US economic growth, limiting fiscal headroom and fuelling inflation. In this context, we think fixed income investors should approach US Treasuries with caution and look to immunise their portfolios from these threats.

An ominous fiscal outlook

The federal deficit has risen over the past decade as rising entitlement costs – primarily social security, Medicaid and Medicare – have outpaced tax revenues.2 In 2024, spending exceeded receipts by US$1.8tn, equivalent to 6.3% of US GDP.3

Looking ahead, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that mandatory government spending on social security and healthcare will grow by 2% of GDP, combined, between 2024 and 2034.4 This reflects demographics, as the baby boomer generation approaches old age, and the rising costs of delivering healthcare.

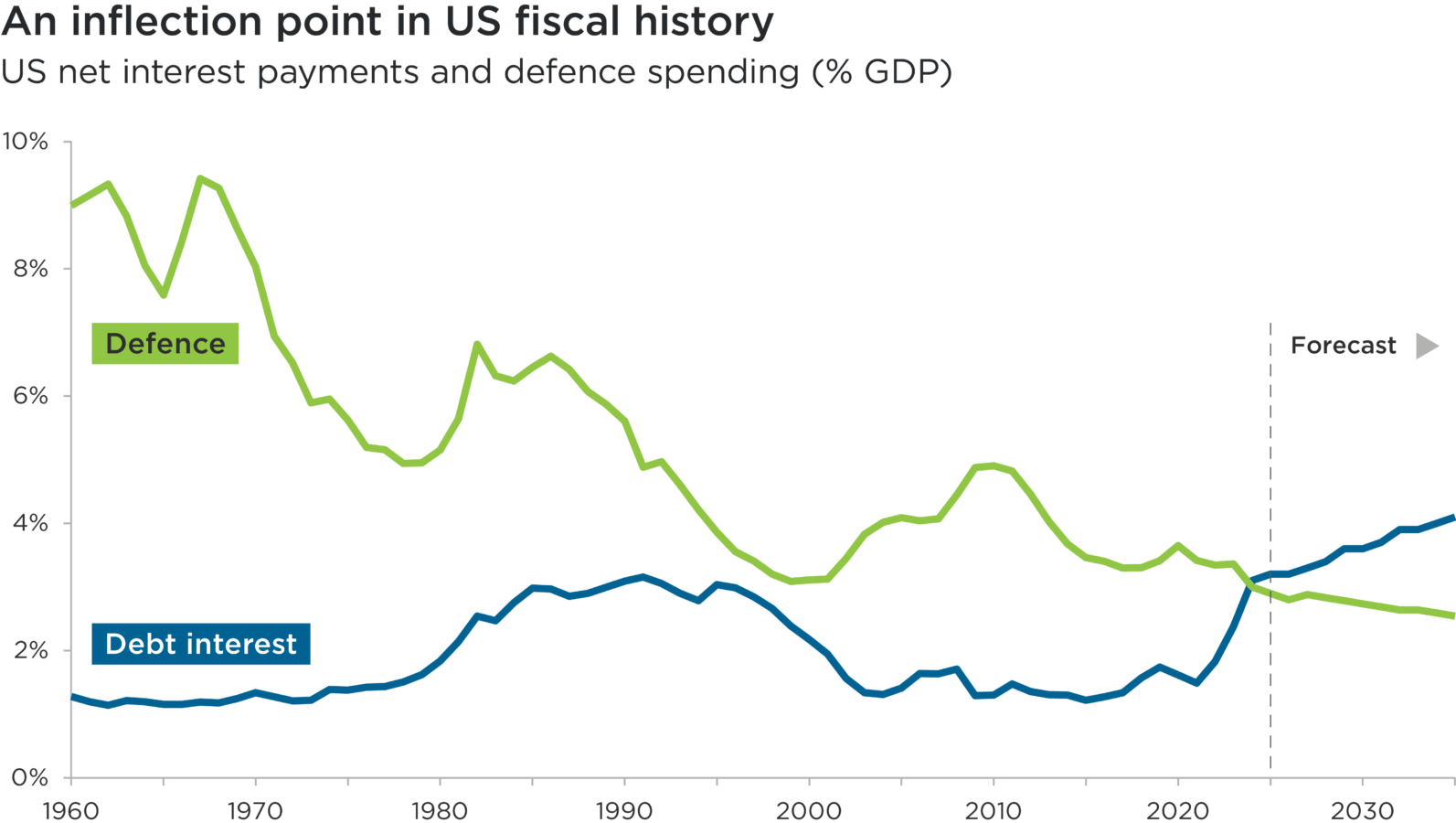

More concerningly, net interest costs are the fastest-growing major category of federal expenditure. Quarterly interest payments have almost doubled over the past three years and equated to 3.1% of GDP in 2024, overtaking defence spending.5

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, March 2025; Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2024; Congressional Budget Office, January 2025. Forecasts for defence spending from 2027 are extrapolated using the assumption that it remains 48% of total discretionary US federal spending (the average from 2014 to 2023).

Subhead: US net interest payments and defence spending (% GDP)

Overview: This line chart compares US federal spending on defence and debt interest payments, as a percentage of US GDP, between 1960 and 2035. Data from 2025 to 2035 is forecast.

This chart shows that the value of debt interest payments overtook defence spending for the first time in 2024. Debt interest has risen sharply since 2021, while defence spending has continued on a downward trajectory.

There are two overarching drivers of rising interest costs. First, the growing deficit itself: US national debt now exceeds US$36tn, having soared since the global financial crisis and, more recently, during the pandemic.6 Second, an extended period of low interest rates has ended: in November 2020, 10-year Treasury bonds were issued at 0.875%. In February 2025, the same bonds were issued at 4.625%.7

These factors interrelate, of course: the size of the national debt means higher borrowing costs have a more material impact on the US fiscal position.

Why does it matter?

Governments that run sustained deficits rely on creditors’ confidence that debts will be serviced and repaid. Large structural deficits and rising national debts increase the risk of default, but this must remain an extremely unlikely event for the US given its economic strength and because debt is issued in US dollars.

A greater concern is that the deficit and debt undermine US economic growth in two ways. First, high levels of government borrowing can distort markets and ‘crowd out’ corporate borrowing, potentially limiting the amount of money available for the private sector to allocate productively. Second, government spending on debt servicing cannot have the same multiplier effect in the economy as forms of fiscal spending that support employment.

Persistent deficits in the context of high national debt also threaten to undermine economic resilience and restrict the government’s ability to respond to future economic crises or make long-term investments in infrastructure. They can also contribute to elevated interest rates if investors begin to demand a higher risk premium and if the supply of government bonds exceeds demand.

Finally, higher debt adds to inflationary pressures in both the short and the long-run. It is estimated that a permanent deficit increase of 1% of GDP – roughly the cost of extending individual tax cuts – equates to a loss in household purchasing power of US$300 to US$1,250 after five years.8

Can the deficit be tamed?

There are three ways that the deficit could be reduced: spending cuts, higher taxes or lower interest rates.

Cutting government spending appears to be a central theme of the Trump administration, as illustrated by the creation of the headline-grabbing Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Without reform to entitlements – the ‘third rail of American politics’ (so-called because they are politically lethal to touch) – the stated goal of achieving US$2tn in annual savings will be hard to achieve.

Raising taxes seems less likely under this administration. Trade tariffs, depending on their scope, size and duration, could contribute up to US$1.3tn to the federal budget over the next decade.9 It has also been suggested that endowments could be taxed. Both would however be overshadowed by the proposed extension to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which would reduce federal tax revenue by US$4.5tn from 2025 to 2034.10

Lowering interest rates will also be a hard task. A pro-growth agenda will generally be inflationary and so likely to put upward pressure on rates. There has been recent speculation that creditors would be asked to convert their Treasuries into zero-coupon 100-year bonds. This reported proposal forms part of a so-called ‘Mar-a-Lago accord’ to help weaken the US dollar and provide cheap, low-cost financing to the US government under threat of tariffs or loss of security guarantees.11 As well as seeming far-fetched, the proposals would likely prove ineffectual.12

How can Treasury investors immunise their portfolios?

In the near term, we do not believe that investors in US Treasuries should be overly alarmed. Medium-to-long-term, however, the unsustainable growth of federal debt throughout the economic cycle is concerning. Any economic slowdown could prove very challenging.

We look to hedge some of these tail risks through a couple of strategies. The first is to have a structural underweight allocation to US Treasuries, preferring other high-quality, liquid ‘AAA’-rated alternatives. Among those are issuances from large multilateral development banks, like the European Investment Bank and the World Bank, which are backed in different ways by their member states. The KfW is an example of a development bank whose debt is government-backed, in its case by Germany.

The second strategy is to skew allocations to low coupon Treasuries. This would help lower risk in any scenario where the US government renegotiates with creditors and lowers the coupon on outstanding Treasuries. This remains a very low (though not zero) probability event, but the cost in terms of lower liquidity is minimal.

Approaching Treasuries with caution

The US’s fiscal trajectory raises significant longer-term concerns for investors in Treasuries. Rising budget deficits, escalating interest costs and the swelling national debt combine to underscore the need for cautious portfolio management, including some diversification of strategy, to navigate the risk of US recession – and even, however remotely, the possibility of default.

1 US Treasury, March 2025: What is the national debt?

2 US Treasury, March 2025: What is the national deficit?

3 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, February 2025: Federal Government Debt

4 Congressional Budget Office, January 2025: The Budget and Economic Outlook, 2025 to 2035

5 Congressional Budget Office, January 2025: The Budget and Economic Outlook, 2025 to 2035

6 US Treasury, March 2025: What is the national debt?

7 Bloomberg, March 2025

8 The Budget Lab at Yale, 12 March 2025: The Inflationary Risks of Rising Federal Deficits and Debt

9 Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, February 2025: How Much Revenue Will Trump’s Tariffs Raise?

10 Tax Foundation, March 2025: Budget Reconciliation: Tracking the 2025 Trump Tax Cuts

11 Bloomberg, 21 February 2025: ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’ Chatter is Getting Wall Street’s Attention

12 Sobel, M., 6 December 2024. No realistic foundation for a Mar-a-Lago Accord. OMFIF

References to specific securities are for illustrative purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation to buy or sell. Nothing presented herein is intended to constitute investment advice and no investment decision should be made solely based on this information. Nothing presented should be construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell a particular type of security or follow any investment technique or strategy. Information presented herein reflects Impax Asset Management’s views at a particular time. Such views are subject to change at any point and Impax Asset Management shall not be obligated to provide any notice. Any forward-looking statements or forecasts are based on assumptions and actual results are expected to vary. While Impax Asset Management has used reasonable efforts to obtain information from reliable sources, we make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of third-party information presented herein. No guarantee of investment performance is being provided and no inference to the contrary should be made.

United States

United States